Chapter 2 : Partnerships for Watershed Management

2.1 Introduction

2.2 Reservoir Managers versus Watershed Management

2.3 Common Watershed Problems

2.4 Links between Watersheds and Reservoir Fish

2.5 Iowa's Lake and Watershed Management Program

2.6 Tennessee Valley Authority's Watershed Partnerships

2.7 Watershed Management

2.7.1 The Necessity of Watershed Management

2.7.2 Goal of Watershed Management

2.7.3 Watershed Inventory

2.7.4 Partnership Building

2.7.5 Watershed Management Practices

2.1 Introduction

A watershed is the geographical area that drains into a reservoir, and thus a natural geographical unit for the management of water resources (Figure 2.1). Water- shed land cover and land use is a major determinant of water quality, hydrology, and, thereby, fish community composition. A watershed contributes nutrients to a reservoir and subsequently influences primary production. Nutrients, especially phosphorus and nitrogen, flow to the reservoir from all parts of the watershed by way of streams, surface runoff, and groundwater. Typically, watersheds experience various levels of deforestation, agricultural development, industrial growth, urban expansion, surface and subsurface mining activities, water diversion, and road construction. These changes destabilize runoff, change annual amplitudes and distributions of flow, and increase downstream movement of nutrients, sediment, and detritus, which ultimately are trapped by reservoirs. Depending on their extent, inputs can regulate primary productivity, species assemblages, and food web interactions and control most all biogeochemical and ecological processes.

Generally, reservoir fish managers lack expertise and jurisdiction to operate outside the reservoir and therefore have to partner with watershed-level organizations. Partnering with these organizations can provide the structure needed to plan, fund, and complete restoration work and may give reservoir fish managers the political clout they normally do not have outside the reservoir.

Over the last two decades watershed management organizations have shown unprecedented growth across the USA. Some of these are small and local, whereas others are basinwide or statewide. An example is the Geist–Fall Creek Watershed Alliance in central Indiana, which is focused on the improvement and protection of Geist Reservoir’s water quality to alleviate fish kills (Figure 2.2). Its watershed management plan includes a watershed inventory, critical areas, goals, best management practices (BMPs), and effectiveness tracking (GWA 2011). Another example is the Cedar Creek Reservoir Watershed Partnership in north–central Texas, also formed to protect the reservoir (TWRI 2007). In this partnership reservoir fish managers participate as members of a technical advisory group. Watershed organizations differ geographically given the diversity of landscapes as well as parallel diversity in the cultural, political, and economic scene. Thus, it is unlikely that a standard model for participation by reservoir managers in watershed organizations is workable in all localities.

2.2 Reservoir Managers versus Watershed Management

It is pertinent to ask what strategic role reservoir fish managers might play in landscape partnerships. As partners, managers can be equipped to show the linkages between the reservoir and disturbances in the watershed and to be activists for change in the watershed that benefits fish in the reservoir. Managers may be prepared to contribute information suitable for developing restoration and protection plans, particularly relevant to how specific actions may affect sediment and nutrient inputs into the reservoir and subsequently fish communities.

As partners, reservoir management agencies contribute human resources with varied skills, abilities, experience, and technical expertise about reservoir management to the collaboration. These agency resources can have varying effects on the partnership's efforts, depending on the particular circumstances that brought the partners to the table. Sometimes agency technical expertise can help the group understand ecological processes and develop innovative plans for management. At other times, technical expertise could get in the way, such as when it is backed with an attitude that experts know best and others have little to contribute.

Back to top

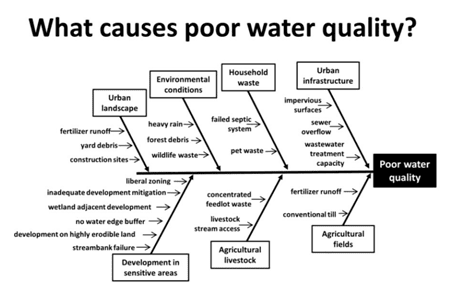

2.3 Common Watershed Problems

Become a Contributing Sponsor

Become a part of projects that need your support.